Thinking about Administrative Justice: the Power of Mashaw’s Models

There are many available definitions of administrative justice, a term which “has, until recently, been shrouded in obscurity”[1] and provoked “considerable disagreement”.[2]

On the one hand, the term can be used to denote “the justice inherent in decision making”,[3] or “those qualities of decision making process that provide arguments for the acceptability of its decisions”.[4] Here, the individual at the receiving end of public services is the central focus.[5]

On the other hand, it is sometimes used to refer to the “the overall system by which decisions of an administrative or executive nature are made in relation to particular persons, including (a) the procedures for making such decisions, (b) the law under which such decisions are made, and (c) the systems for resolving disputes and airing grievances in relation to such decisions”.[6] Here, the ensemble of decision-making and grievance-resolution mechanisms is treated as key.

Somewhere between the two lies the UK Administrative Justice Institution’s definition of administrative justice: “how government and public bodies treat people, the correctness of their decisions, the fairness of their procedures and the opportunities people have to question and challenge decisions made about them”.[7]

This definitional disagreement does not necessarily mean that the concept of administrative justice is inherently vague or essentially contested. The making and reviewing of administrative decisions and the construction of mechanisms for ensuring decisional accuracy covers a vast terrain. This terrain ranges from front-line officials (who make decisions and may feed information back to their managers about on-the-ground realities) through their hierarchical superiors (who may review front-line decisions, generate institutional guidelines and, more broadly, foster institutional understandings to enhance decisional accuracy) and all the way to adjudicative mechanisms designed to resolve disputes between individuals and public bodies. Moreover, in any given administrative decision-making setting, there are potentially infinite variations in the particular lie of the land. Given the scope and complexity of the terrain, definitional disagreement most likely arises because different authors focus on different parts of the terrain: the individual receiving services, for instance, versus the system as an ensemble.

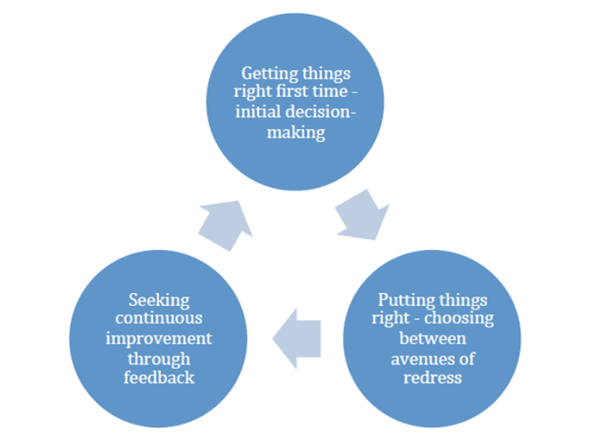

In the Administrative Justice and Tribunals Council Landscape Paper, the administrative justice system was envisaged as a virtuous circle:

In the same vein, Buck, Kirkham and Thompson envisage three strands to administrative justice, which map neatly onto this visualisation: getting it right, putting it right and setting it right.[8] Woven together, these three strands cover the whole of the vast terrain of administrative justice, both the “myriad of first-instance decisions” and the “smaller number of decisions that are the subject of an appeal or a complaint”, as well as the “methods that are intended to improve first-instance decision-making”.[9]

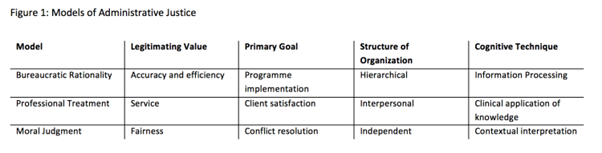

In Bureaucratic Justice: Managing Social Security Disability Claims,[10] Professor Jerry Mashaw set out three influential “models” of administrative justice, which have “attracted many commentators” because of the models’ “resonance with real world experiences of administrative systems”.[11] These can be visualised as follows:

Further iterations have been suggested by Michael Adler[13] and Robert Kagan.[14]

Adler argues, for instance, that models associated with the rise of New Public Management need to be incorporated into Mashaw’s schema.[15] He calls these managerial, consumerist and market. But these models of “[n]ew and better forms of management”[16] are more closely related to internal management and redress systems than to front-line interactions between decision-makers and individuals.[17] Adler’s concerns about “different forms of financial and management audit” and “better quality services through the publication of service standards, the tighter regulation of services, and the details of complaints procedures” [18] are best understood as relating to “putting it right” and “setting it right”. It is true that the “acceptability of front-line decisions” might occasionally be enhanced by respect for the “tents” of managerialism or consumerism,[19] but this is best understood as a by-product of the influence of these models within the organizational structure rather than as a direct attempt to regulate front-line decision-making.[20] The replacement of human decision-making with market-based forms of resource allocation is, admittedly, an exception and can be conceived of as an additional administrative justice model. But the displacement of humans by market mechanisms really is a separate topic to the rise of artificial administration.

It is difficult to improve upon Mashaw’s models when analysing front-line decision-making. Mashaw’s models may come up short inasmuch as they exert little analytical bite on the “putting it right” and “setting it right” components of the virtuous circle, but for the purposes of understanding “how individuals should be treated”[22] Mashaw’s focus on “processes which produce decisions”[23] yields extremely useful models and, indeed, “normative tool[s] which can be used to scrutinise and assess” new modes of decision-making.[24]

[1] Michael Adler, “Introduction” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), at p. xv.

[2] Michael Harris and Martin Partington eds., Administrative Justice in the 21st Century (Hart, Oxford, 1999), at p. 2.

[3] Michael Adler, “Understanding and Analyzing Administrative Justice” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), p. 129, at p. 129.

[4] Jerry Mashaw, Bureaucratic Justice: Managing Social Security Disability Claims (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1983). But Mashaw’s models are too narrow for that purpose: both redress systems and internal management systems contribute to arguments for the “acceptability” of decisions. Michael Adler, “A Socio-Legal Approach to Administrative Justice” (2003) 25 Law and Policy 323, at p. 329.

[5] See also Simon Halliday, Judicial Review and Compliance with Administrative Law (Hart, Oxford, 2004), at p. 114, referring to “normative and legal conceptions of the aims, values and focus of decision-making within government agencies”.

[6] Tribunals Courts and Enforcement Act 2007, Sch. 7 para 13(4), repealed by The Public Bodies (Abolition of Administrative Justice and Tribunals Council) Order 2013 (S.I. 2013/2042), art. 1(2), Sch. para. 36:

[7]A Research Roadmap for Administrative Justice (Nuffield Foundation, 2018), at p. 5.

[8] The Ombudsman Enterprise and Administrative Justice (Ashgate, Surrey, 2011), at p. xxx. Jh.l.91b.

[9] Michael Adler, “Understanding and Analyzing Administrative Justice” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), p. 129, at pp. 153-154.

[10] Yale University Press, New Haven, 1983.

[11] Roy Sainsbury, “Administrative Justice, Discretion and the ‘Welfare to Work’ Project” (2008) 30 Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law 323, at p. 325.

[12] Joe Tomlinson and Robert Thomas, “Administrative justice – A primer for policymakers and those working in the system” UK Administrative Justice Institute (September 9, 2016).

[13] “A Socio-Legal Approach to Administrative Justice” (2003) 25 Law & Policy 323.

[14] “Varieties of Bureaucratic Justice” in Nicolas Parrillo ed., Administrative Law from the Inside Out: Essays on the Themes in the Work of Jerry Mashaw (Cambridge UP, 2016). See also Marc Hertogh, “Through the Eyes of Bureaucrats: How Front-line Officials Understand Administrative Justice” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), p. 203, at p. 217, distinguishing four different types of “legal citizenship”; and Simon Halliday and Colin Scott, “A Cultural Analysis of Administrative Justice” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), p. 183, at p. 192, setting out a “cultural typology” of administrative justice.

[15] “A Socio-Legal Approach to Administrative Justice” (2003) 25 Law & Policy 323.

[16] Michael Adler and Paul Henman, “Justice Beyond the Courts: The Implications of Computerisation for Procedural Justice in Social Security” in Agustí Cerrillo i Martínez and Pere Fabra i Abat, E-Justice: Information and Communication Technologies in the Court System (Information Science Reference, New York, 2008), 65, at p. 69.

[17] The same can be said of Kagan’s focus on institutional culture: “Varieties of Bureaucratic Justice” in Nicolas Parrillo ed., Administrative Law from the Inside Out: Essays on the Themes in the Work of Jerry Mashaw (Cambridge UP, 2016).

[18] Michael Adler and Paul Henman, “Justice Beyond the Courts: The Implications of Computerisation for Procedural Justice in Social Security” in Agustí Cerrillo i Martínez and Pere Fabra i Abat, E-Justice: Information and Communication Technologies in the Court System (Information Science Reference, New York, 2008), 65, at p. 69.

[19] Michael Adler, “Understanding and Analyzing Administrative Justice” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), p. 129, at p. 150.

[20] See also Simon Halliday and Colin Scott, “A Cultural Analysis of Administrative Justice” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), p. 183, at p. 194: “even though medical practitioners may be the subject of customer satisfaction surveys, their decision making as doctors may still comprise the application of expertise. Equally, although public agencies may have to provide services in a competitive environment and so be incentivised (perhaps financially) to improve the customer experience, alterations may not relate to the actual mode of decision making, but rather to additional aspects[s] of service delivery such as waiting times, courtesy, clarity of communication, and so forth”.

[21] See further Cane.

[22] Michael Adler and Paul Henman, “Justice Beyond the Courts: The Implications of Computerisation for Procedural Justice in Social Security” in Agustí Cerrillo i Martínez and Pere Fabra i Abat, E-Justice: Information and Communication Technologies in the Court System (Information Science Reference, New York, 2008), 65, at p. 70.

[23] Simon Halliday and Colin Scott, “A Cultural Analysis of Administrative Justice” in Michael Adler ed., Administrative Justice in Context (Hart, Oxford, 2010), p. 183, at p. 184.

[24] Roy Sainsbury, “Administrative Justice, Discretion and the ‘Welfare to Work’ Project” (2008) 30 Journal of Social Welfare & Family Law 323, at p. 327.

This content has been updated on October 31, 2019 at 02:33.